October 1944 continues and my father, Seaman First Class, John Thomas Ryan is still serving on the USS Hornet (CV-12).

20-26 Oct 1944 – Strikes on Leyte supporting invasion of the Philippines as stated in the ships log for the USS Hornet (CV-12).

In my previous post I wrote about the Second Battle of the Philippine Sea (Leyte Gulf). The Battle of Leyte Gulf, also called the Battles for Leyte Gulf, and formerly known as the Second Battle of the Philippine Sea, is generally considered to be the largest naval battle of World War II and, by some criteria, possibly the largest naval battle in history. Since the Battle of Leyte Gulf consisted of four separate engagements between the opposing forces: the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, the Battle of Surigao Strait, the Battle of Cape Engaño and the Battle off Samar, as well as other actions, I decided to break the story into multiple parts. In Part 1, I covered the background and the submarine action in Palawan passage on October 23, 1944. In Part 2, I wrote about the Battle of Sibuyan Sea. In Part 3, I wrote about Admiral Halsey’s decisions and the San Bernardino Strait. For Part 4, I wrote about the Battle of Surigao Strait. For Part 5, the Battle of Samar. For Part 6, the Battle Cape Engaño. For this final installment in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, I will write about the criticisms of Admiral Halsey (some of which I mentioned throughout), a recap the losses experienced by all participants in these critical battles and the aftermath.

Bull’s Run

Among the criticism of Halsey in the Battle of Leyte Gulf was his decision to take TF 34 north in pursuit of Ozawa, and for failing to detach it when Kinkaid first appealed for help.

A piece of US Navy slang for Halsey’s actions is Bull’s Run, a phrase combining Halsey’s newspaper nickname “Bull” (in the US Navy he was known as “Bill” Halsey) with an allusion to the Battle of Bull Run in the American Civil War. There were two battles of Bull Run (Manassas) but maybe the slang referred to both.

In his dispatch after the battle, Halsey justified the decision as follows:

-

- Searches by my carrier planes revealed the presence of the Northern carrier force on the afternoon of 24 October, which completed the picture of all enemy naval forces. As it seemed childish to me to guard statically San Bernardino Strait, I concentrated TF 38 during the night and steamed north to attack the Northern Force at dawn.

-

- I believed that the Center Force had been so heavily damaged in the Sibuyan Sea that it could no longer be considered a serious menace to Seventh Fleet.

Halsey also argued that he had feared leaving TF 34 to defend the strait without carrier support as that would have left it vulnerable to attack from land-based aircraft, while leaving one of the fast carrier groups behind to cover the battleships would have significantly reduced the concentration of air power going north to strike Ozawa.

Admiral Lee said after the battle that he would have been fully prepared for the battleships to cover the San Bernardino Strait without ‘any’ carrier support. Moreover, if Halsey had been in proper communication with 7th Fleet, it would have been entirely practicable for the escort carriers of TF 77 to provide adequate air cover for TF 34—a much easier matter than it would be for those escort carriers to defend themselves against the onslaught of Kurita’s heavy ships.

It may be argued that the fact that Halsey was aboard one of the battleships, and “would have had to remain behind” with TF 34 (while the bulk of his fleet charged northwards to attack the Japanese carriers), may have contributed to this decision, but this is in all likelihood a minor point.

It has been pointed out that it would have been perfectly feasible (and logical) to have taken one or both of 3rd Fleet’s two fastest battleships (Iowa and/or New Jersey) with the carriers in the pursuit of Ozawa, while leaving the rest of the battle line off the San Bernardino Strait (indeed, Halsey’s original plan for the composition of TF 34 was that it would contain only four, not all six, of the 3rd Fleet’s battleships); thus, guarding the San Bernardino Strait with a powerful battleship force would not have been incompatible with Halsey personally going north aboard New Jersey.

Probably a more important factor was that Halsey was philosophically against dividing his forces; he believed strongly in concentration as indicated by his writings both before World War II and in his subsequent articles and interviews defending his actions. In addition, Halsey may well have been influenced by the criticisms of Admiral Raymond Spruance, who was widely thought to have been excessively cautious at the Battle of the Philippine Sea and so allowed the bulk of the Japanese fleet to escape. Halsey was also likely influenced by his Chief of Staff, Rear Admiral Robert “Mick” Carney, who was also wholeheartedly in favor of taking all of 3rd Fleet’s available forces northwards to attack the Japanese carrier force.

However, Halsey did have reasonable and, in his view, given the information he had available, practical reasons for his actions.

- Halsey believed Admiral Kurita’s force was more heavily damaged than it was. While it has been suggested that Halsey should have taken Kurita’s continued advance as evidence that his force was still a severe threat, this view cannot be supported given the well-known propensity for members of the Japanese military to persist in hopeless endeavors to the point of suicide. So, in Halsey’s estimation, Kurita’s weakened force was well within the ability of Seventh Fleet to deal with, and did not justify dividing his force.

- Halsey did not comprehend just how badly compromised Japan’s naval air power was and that Ozawa’s decoy force was nearly devoid of aircraft. Halsey, in a letter to Admiral Nimitz on 22 October 1944 (three days before the Battle off Samar) wrote that Admiral Marc Mitscher believed “Jap naval air was wiped out.” Mitscher, with Admiral Spruance at the Battle of the Philippine Sea (the Marianas Turkey Shoot) drew his conclusion from the very poor performance of the Japanese. Halsey ignored Mitscher’s insights, and made an understandable and, to him, prudent threat-conservative judgment that Ozawa’s force was still capable of launching serious attacks. Halsey later explained his actions partly by explicitly stating he did not want to be “shuttle bombed” by Ozawa’s force (a technique whereby planes can land and rearm at bases on either side of a foe, allowing them to attack on both the outbound flight and the return), or to give them a “free shot” at the US forces in Leyte Gulf. He was obviously not similarly concerned with giving Kurita’s battleships and cruisers a free shot at those same forces.

The fact that Halsey made one seemingly prudent threat-conservative judgment regarding Ozawa’s aircraft carriers and another rather opposite judgment regarding Kurita’s battleships probably reflects his understandable bias toward aircraft carriers as the prime threat of the war. At Leyte Gulf, Halsey failed to appreciate that under certain circumstances battleships and cruisers could still be extremely dangerous, and ironically, through his own failures to adequately communicate his intentions, he managed to bring those circumstances about.

Clifton Sprague—commander of Task Unit 77.4.3 in the battle off Samar—was later bitterly critical of Halsey’s decision, and of his failure to clearly inform Kinkaid and 7th Fleet that their northern flank was no longer protected:

In the absence of any information that this exit [of the San Bernardino Strait] was no longer blocked, it was logical to assume that our northern flank could not be exposed without ample warning.

In his book, The History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Samuel Eliot Morrison wrote the following regarding Halsey’s failure to turn TF 34 southwards when 7th Fleet’s first calls for assistance off Samar were received:

If TF 34 had been detached a few hours earlier, after Kinkaid’s first urgent request for help, and had left the destroyers behind, since their fueling caused a delay of over two and a half hours, a powerful battle line of six modern battleships under the command of Admiral Lee, the most experienced battle squadron commander in the Navy, would have arrived off the San Bernardino Strait in time to have clashed with Kurita’s Center Force… Apart from the accidents common in naval warfare, there is every reason to suppose that Lee would have “crossed the T” and completed the destruction of Center Force.

Instead, the mighty gunfire of the Third Fleet’s Battle Line, greater than that of the whole Japanese Navy, was never brought into action except to finish off one or two crippled light ships.

—Morison (1956), pp. 336–337

Perhaps the most telling comment is made with just a few words by Vice Admiral Lee in his action report as Commander of TF 34 —

No battle damage was incurred nor inflicted on the enemy by vessels while operating as Task Force Thirty-Four.

—Task Force 34 Action Report: 6 October 1944 – 3 November 1944

Losses

The losses in the battle of Leyte Gulf were not evenly distributed throughout all forces; for instance, the destroyer USS Heermann—despite her unequal fight with the enemy—finished the battle with only six of her crew dead. More than 1,000 sailors and aircrewmen of the Allied escort carrier units were killed. As a result of communication errors and other failures, a large number of survivors from Taffy 3 were unable to be rescued for several days, and died unnecessarily as a consequence.

Due to the long duration and size of the battle, accounts vary as to the losses which occurred as a part of the Battle of Leyte Gulf and losses that occurred shortly before and shortly after. One account of the losses lists the following vessels:

Allied losses

The United States lost six front line warships during the Battle of Leyte Gulf:

- One Light Carrier: USS Princeton

- Two Escort Carriers: USS Gambier Bay and St. Lo (the first major warship sunk by a kamikaze attack)

Gambier Bay (CVE-73) under Japanese fire during the Battle of Samar. The smudge in the upper right corner is a Japanese heavy cruiser. US Navy photo. img URL: http://www.navsource.org/archives/03/0307304.jpg

- Two Destroyers: Hoel and Johnston

Battle off Samar, 25 October 1944

American survivors of the battle are rescued by a U.S. Navy ship on 26 October 1944.

Some 1200 survivors of USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73), USS Hoel (DD-533), USS Johnston (DD-557) and USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413) were rescued during the days following the action.

Photographed by U.S. Army Private William Roof.

Photograph from the Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

- One Destroyer Escort: USS Samuel B. Roberts

- Four other American ships were damaged.

Japanese losses

The Japanese lost 26 front-line warships during the Battle of Leyte Gulf:

- One Fleet Aircraft Carrier: Zuikaku (flagship of the decoy Northern Forces).

- Three Light Aircraft Carriers: Zuihō, Chiyoda, and Chitose.

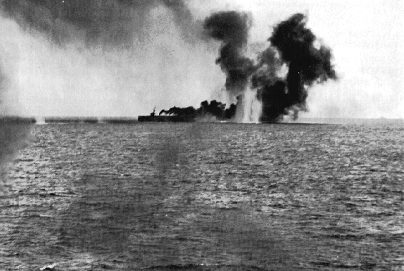

his light carrier of the Japanese NavyÂ’s Chitose Class lies dead in the waters off Luzon following attacks by Helldivers and Avengers on 24 October 1944

- Three Battleships: Musashi (former flagship of the Japanese Combined Fleet), Yamashiro (flagship of the Southern Force) and Fusō.

- Six Heavy Cruisers: Atago (flagship of the Center Force), Maya, Suzuya, Chokai, Chikuma, and Mogami.

- Four Light Cruisers: Noshiro, Abukuma, Tama, and Kinu.

- Nine Destroyers: Nowaki, Hayashimo, Yamagumo, Asagumo, Michishio, Akizuki, Hatsuzuki, Wakaba, and Uranami.

Aftermath

The Battle of Leyte Gulf secured the beachheads of the US Sixth Army on Leyte against attack from the sea.

National Archives 111-SC-349595

General MacArthur and soldiers walk from LSTs through the water onto Leyte Island, Philippines, October 1944.

However, much hard fighting would be required before the island was completely in Allied hands at the end of December 1944: the Battle of Leyte on land was fought in parallel with an air and sea campaign in which the Japanese reinforced and resupplied their troops on Leyte while the Allies attempted to interdict them and establish air-sea superiority for a series of amphibious landings in Ormoc Bay—engagements collectively referred to as the Battle of Ormoc Bay.

The Imperial Japanese Navy had suffered its greatest loss of ships and crew ever. Its failure to dislodge the Allied invaders from Leyte meant the inevitable loss of the Philippines, which in turn meant Japan would be all but cut off from its occupied territories in Southeast Asia. These territories provided resources which were vital to Japan, in particular the oil needed for her ships and aircraft. This problem was compounded because the shipyards and sources of manufactured goods such as ammunition, were in Japan itself. Finally, the loss of Leyte opened the way for the invasion of the Ryukyu Islands in 1945.

The major IJN surface ships returned to their bases to languish, entirely or almost entirely inactive, for the remainder of the war. The only major operation by these surface ships between the Battle for Leyte Gulf and the Japanese surrender was the suicidal sortie in April 1945 (part of Operation Ten-Go), in which the battleship Yamato and her escorts were destroyed by American carrier aircraft.

The first use of kamikaze aircraft took place following the Leyte landings. A kamikaze hit the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia on 21 October. Organized suicide attacks by the “Special Attack Force” began on 25 October during the closing phase of the Battle off Samar, causing the destruction of the escort carrier St. Lo.

J.F.C. Fuller, in his The Decisive Battles of the Western World, writes of the outcome of Leyte Gulf:

The Japanese fleet had [effectively] ceased to exist, and, except by land-based aircraft, their opponents had won undisputed command of the sea.

When Admiral Ozawa was questioned… after the war he replied ‘After this battle the surface forces became strictly auxiliary, so that we relied on land forces, special [Kamikaze] attack, and air power… there was no further use assigned to surface vessels, with the exception of some special ships’.

And Admiral Yonai, the Navy Minister, said he realized the defeat at Leyte ‘was tantamount to the loss of the Philippines.’

As for the larger significance of the battle, he said, ‘I felt that it was the end.’

Months after the battle, the US Navy knew the American public had to be told something. The battle had been too large, involved too many US military personnel and had resulted in too much loss of life just to ignore. To this end, the US Navy provided most of the information to the publication Popular Mechanics to publish an article on the battle showing the American public that the battle had gone exactly as Halsey had planned.

It was several years before the true story of Halsey’s decision to leave the San Bernardino Strait unguarded became known to the American public.